Massachusetts and the Civil War

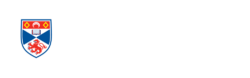

When the former Union soldier Alfred S. Roe set out to document all the Civil War monuments in Massachusetts in 1910, he wrote that: ‘however much Massachusetts has done for the honor of the dead, she has done infinitely more for the living’. Roe’s conclusion is surprising given he went on to record that over 349 monuments and memorials existed in the state. From a boulder marking the spot of early abolitionist meetings in Abington, Plymouth County to the set of marble memorial tablets adorning Millbury, Worcester County’s Town Hall, the commemorative objects Roe itemises seem to attest the state’s commitment to its soldier dead not its neglect of them. Indeed, even he concedes, that ‘still, the record is a proud one, since the excess over one memorial is so great in many of the large towns and in the cities that there is an easy average of more than a single tribute for every one of the three hundred and fifty-four parts into which the Commonwealth is divided’.

Citizen Soldiers

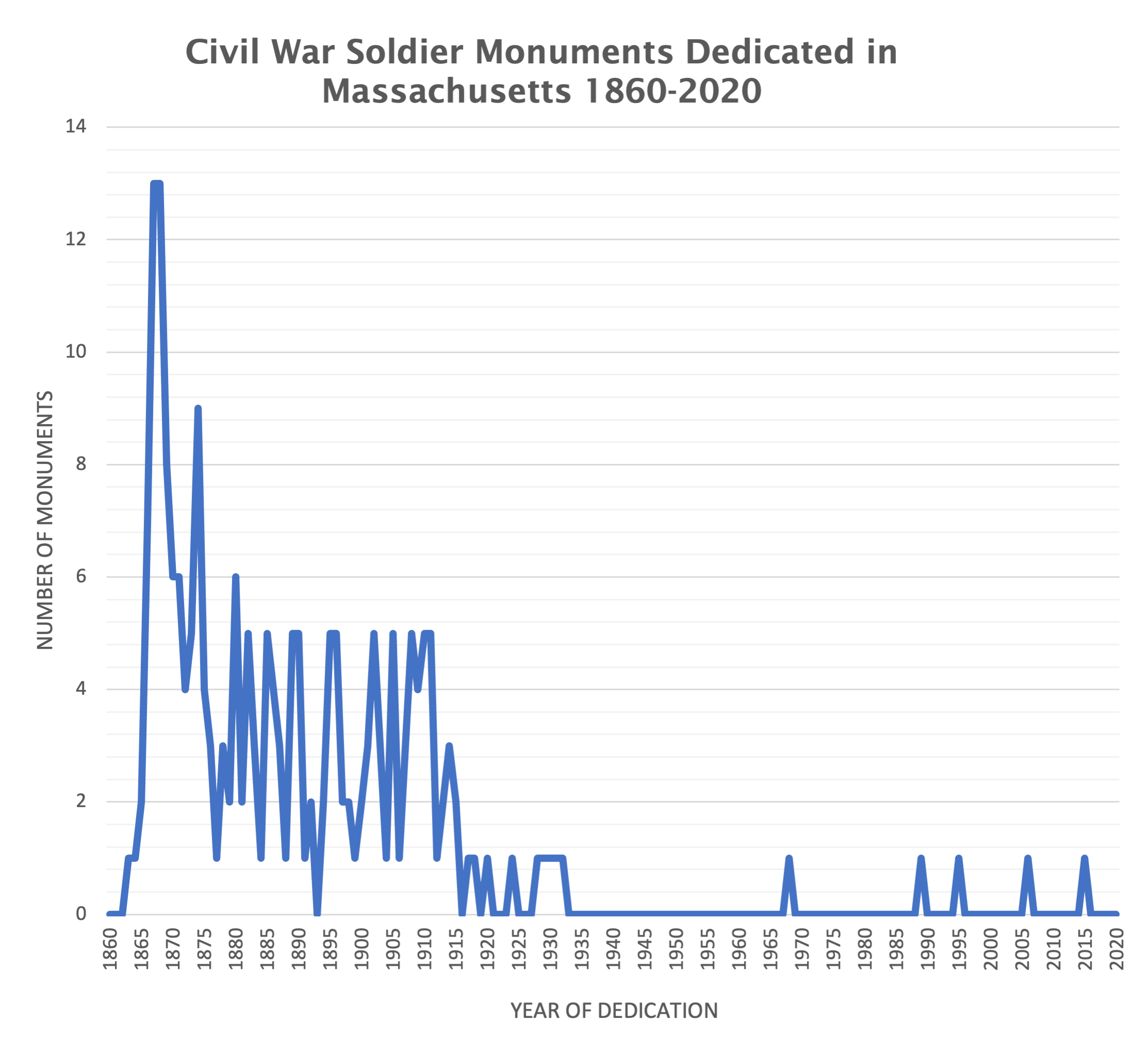

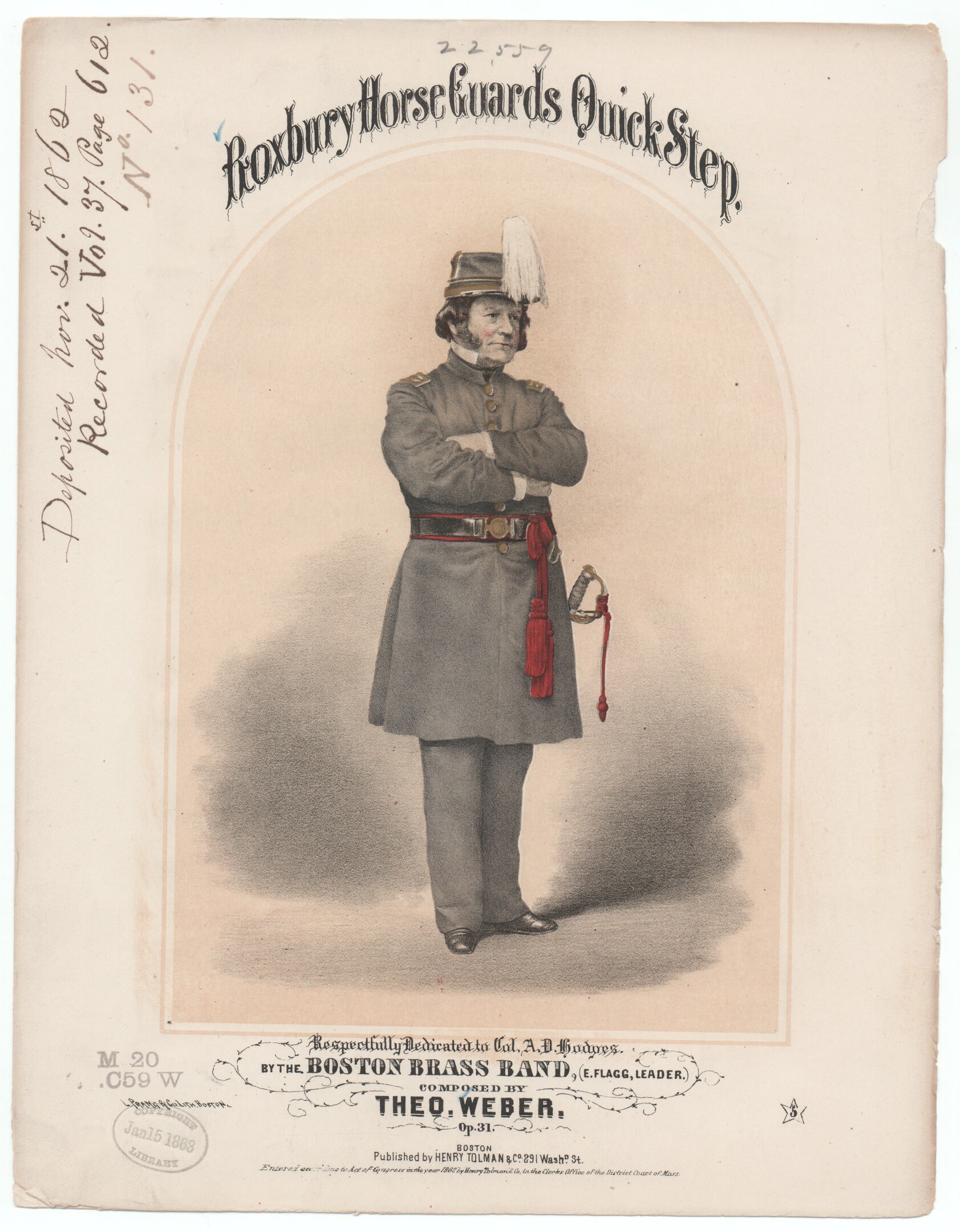

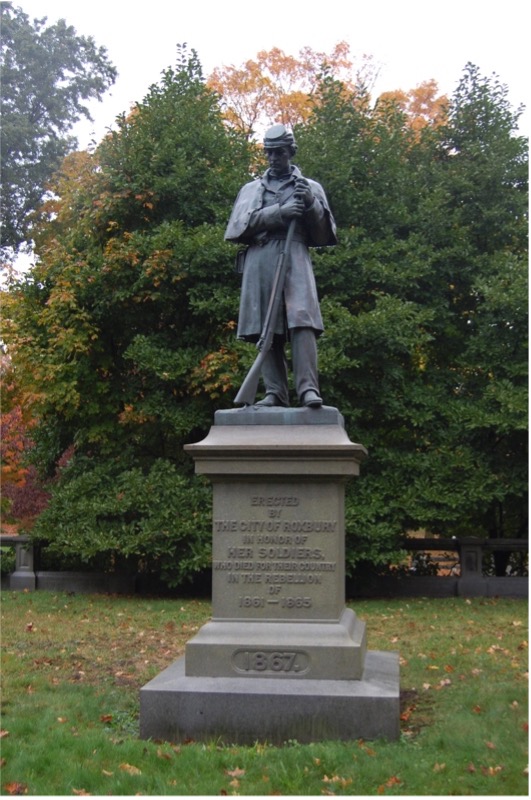

Roe’s main concern, it seems, was to ensure that military service was being adequately honored and that each soldier sacrificed received their due. The majority of Civil War monuments spread across Massachusetts are dedicated to this purpose. Statues of ‘citizen-soldiers’ in fixed poses with rifle in hand can be found in many a town, although the one in the Boston suburb of Roxbury by Martin Milmore is considered the first of its kind, and Theo Alice Ruggles Kitson’s ‘The Volunteer’, located in Newburyport, the first designed by a woman. Local manufacturing industries supported the production of common soldier sculptures like these. One of the most successful in New England was the Ames Manufacturing Company of Chicopee, located in the west of the state. During the war the factory had served as supplier of weaponry for the Union but turned its attention to casting sculpture soon after fighting had ceased. The production of monuments on this scale is indicative of the demand and desire of towns to see soldiers commemorated locally as well as nationally.

The focus on the common soldier figure is often connected to the democratic ideals of the United States at large and their presence in small towns linked to this larger national identity. While monuments to prominent military leaders also exist, this widespread honoring of the average recruit has been interpreted as a populist move. In the context of Massachusetts, the preference is in keeping with the state’s military past and its emphasis on local militia. Widely regarded as the first state to respond to President Lincoln’s call to enlist, the first soldiers to travel to Washington from Massachusetts were known as the ‘Minutemen of ‘61’, a reference to those who had assembled ‘within a minute’ to fight in the American Revolutionary War a century before.

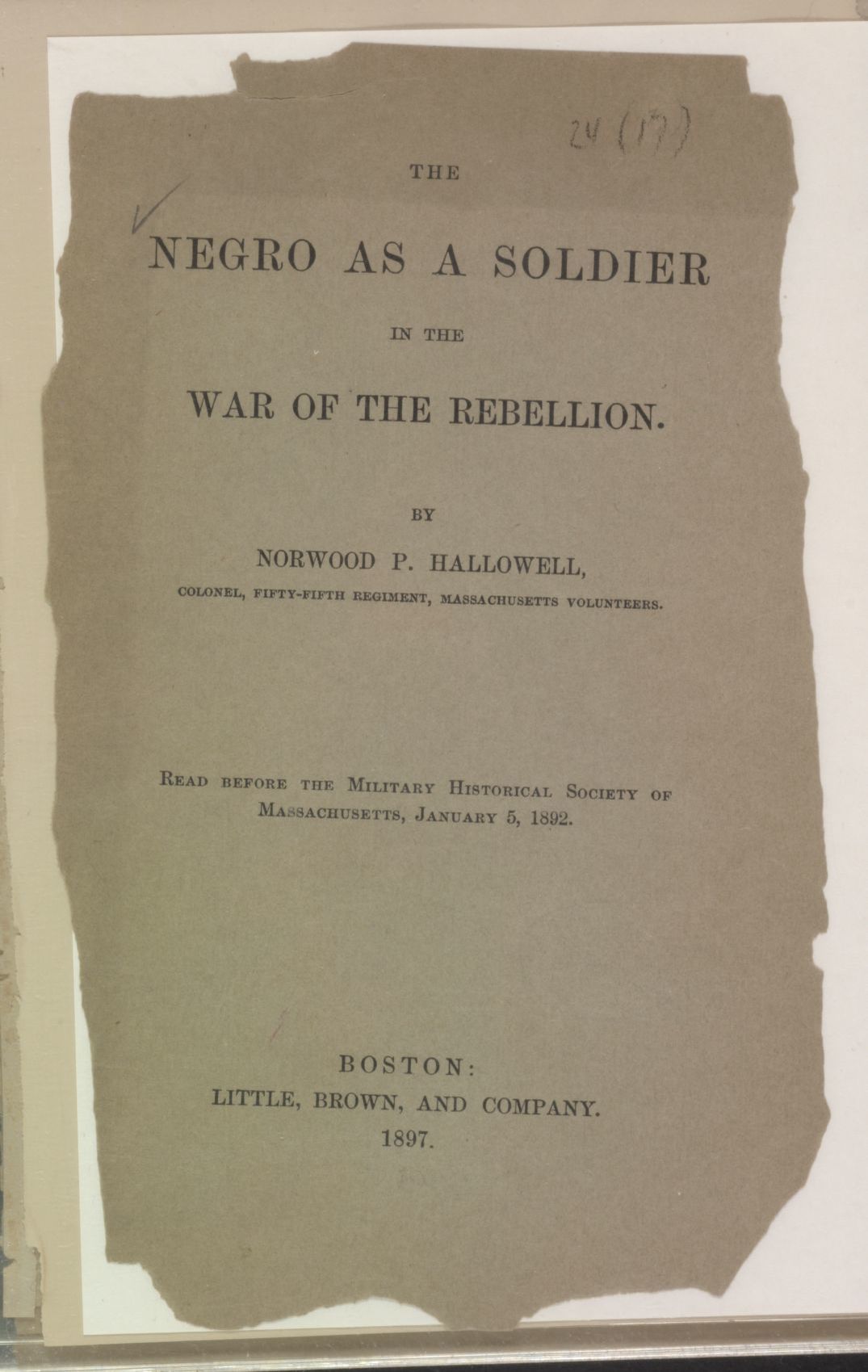

In fact, the state has a notable history of recruitment that has shaped its Civil War identity and its monuments. The organization of one of the first African American regiment, the 54th Massachusetts Volunteers, and the first Irish regiment, the 9th Massachusetts Infantry, took place in the region. Their service is honored at the center of the state’s capital, on the prominent Boston Common and in the nearby Public Garden. In the latter, a statue of Colonel Thomas Cass, commander of the 9th stands on a plinth surrounded by trees and, a few minutes’ walk away, is Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Robert Gould Shaw Memorial, a powerful bronze relief of the 54th heading to battle.

Emancipation and Abolition

The Shaw Memorial is one of Massachusetts’s most famous Civil War monuments. Part of the reason for this is that, unlike others, it acknowledges the fact that African Americans had a role in their own liberation, despite the privileging of Shaw. The abolitionist aims of the Union and centrality of slavery to the war are not always registered in the state’s monuments however. Occasionally, an inscription might read: ‘American Union Preserved/African Slavery Destroyed’, like that on the strange Sphinx in Mount Auburn Cemetery, but far more common is the emphasis on the defense of the Union.

Yet, prior to the outbreak of the war, Massachusetts was a stronghold of abolitionist sentiment. Boston was a major hub on the Underground Railroad and key destination for enslaved people seeking freedom from bondage in the South. Support for the Union stemmed from the anti-slavery movement that flourished in the city and the shelter it provided. While rarer than the common soldier statues, monuments celebrating emancipation and abolition call attention to this past. Early anti-slavery monuments, like Thomas Ball’s controversial Emancipation Group, that features Lincoln singlehandedly freeing a kneeling African American man, or that to the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, identify specific white men as liberators. Later works such as Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s allegorical rendering of the theme, created in 1913 and cast in 1999, foreground its relation to black bodies and the sense of new beginnings. Nearby Fuller’s monument, a further memorial celebrates the Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman; it is titled Step On Board (1999).

Memorial Markers, Spaces, and Places.

While figuration lies at the heart these monuments, the human body is not the only form that commemoration takes in Massachusetts. The ‘Rockery’, a garden-like grotto designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and found in North Easton presents a rather different alternative. Thanks to the use of multiple rocks and their loose assembly, the ‘Rockery’ recalls the tradition of the memorial cairn. A cairn is one of the most basic forms of marker. It is a function they share with the obelisk and the other kinds of shafts that populate the landscape of Massachusetts more broadly. These simple abstract forms were usually less expensive than figurative designs and could be personalised by inscription. Their blank surfaces allowed for the recording of names and other details such as regiment or battle. This is also true of memorial plaques and tablets which, although unassuming at first, could turn a whole building into a monument.

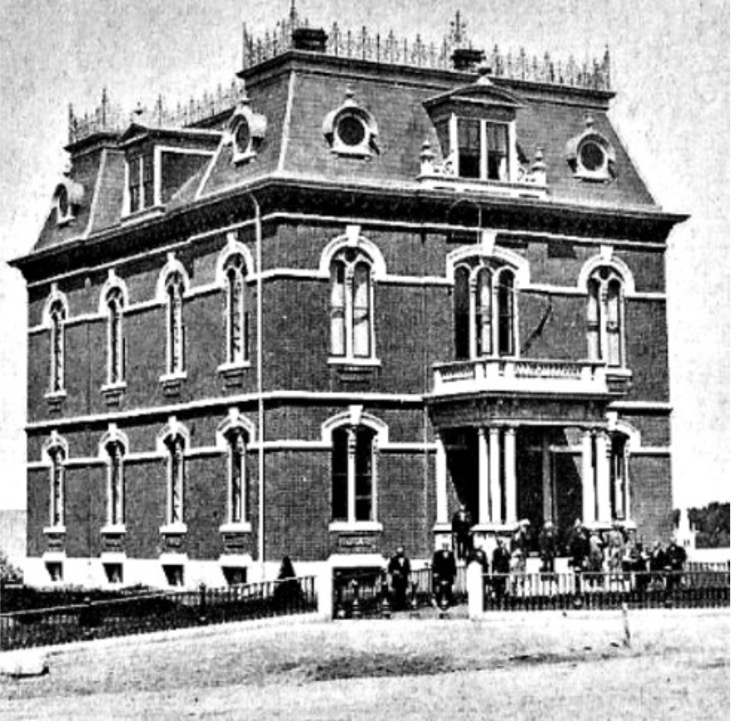

The Town Hall at Sutton in Worcester County is one such example. Memorial tablets were installed in 1885 and list both those who lost their life in the war and those veterans who survived it. Not originally intended as such, the Hall now serves as the town’s main site of Civil War memory. This practice has its counterparts in other Massachusetts towns and taps into the wider debate about ‘useful memorials’.

‘Useful memorials’ were structures that served a civic function in addition to that of remembrance. As early as 1865, The Soldiers’ Memorial Society in Boston expressed a preference for this type. ‘Our monuments to our brothers who have served the country shall be in the hospitals, schools, and other beneficent institutions to which we can contribute in the region where they fought for us,’ they vowed. According to the historian Thomas J. Brown, ‘New England, and especially Massachusetts, dominated the commissioning of utilitarian memorials’ (33). Brown argues that the state’s town system and strong regional leadership created a context in which the combination of memorialisation and municipal building particularly appealed. Public libraries, like those in Andover, Framingham, Lancaster, North Reading, and Northampton, all dedicated between 1868-1875, offer evidence of this trend.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/det.4a13527/)

Those who advocated for utilitarian forms often did so on the belief that monuments should reflect the democratic values the soldiers fought for. To keep their memory alive meant making monuments that had an integral role in the everyday functioning of a town. This kind of thinking also informed the location of more traditional monument forms. It explains why some towns opted to place their monuments on the commons rather than in the local cemetery. As the orator at the dedication of Stockbridge’s monument, Henry Dwight Sedgewick, stated: a monument should not be ‘a thing apart to be visited and admired — not as a stern memento mori – but in the midst of your daily village life, this noble shaft is in your sight as you go to the shop, the post-office, or the bank’. On this basis, the Civil War monuments of Massachusetts tell us something about the connection between memory and the significance of place.

To further explore the place of Civil War monuments in Massachusetts visit the map or delve deeper into the history of an individual monument by clicking one of the icons below.

Resources: